When you pick up a prescription, you might not think twice about whether it’s the brand-name drug or the cheaper generic version. After all, the FDA says they’re the same. But for some people, switching from a brand-name pill to a generic one isn’t just a cost-saving move-it’s a health risk. People report feeling worse after the switch: more fatigue, mood swings, headaches, or even seizures. Why does this happen? And why do some people react badly while others don’t notice a difference?

The Myth of Perfect Equivalence

Generic drugs are required by law to contain the same active ingredient as their brand-name counterparts. That part is true. But what’s not always said is that generics can differ in every other way-fillers, coatings, dyes, and preservatives. These are called inactive ingredients, and they make up 80% to 99% of the pill’s weight. For most people, that doesn’t matter. But for those taking medications with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even tiny changes in how the drug is absorbed can push levels into dangerous territory.NTI drugs are the ones where the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. Think levothyroxine for thyroid conditions, warfarin for blood thinning, or phenytoin for seizures. If your blood level of levothyroxine drops just 10%, your TSH can spike, leaving you exhausted, gaining weight, or depressed. If it goes up too high, you risk heart rhythm problems. A 2019 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that nearly 24% of patients switching from brand-name Synthroid to a generic version had TSH levels move out of the safe range within six months. That’s more than 1 in 5 people.

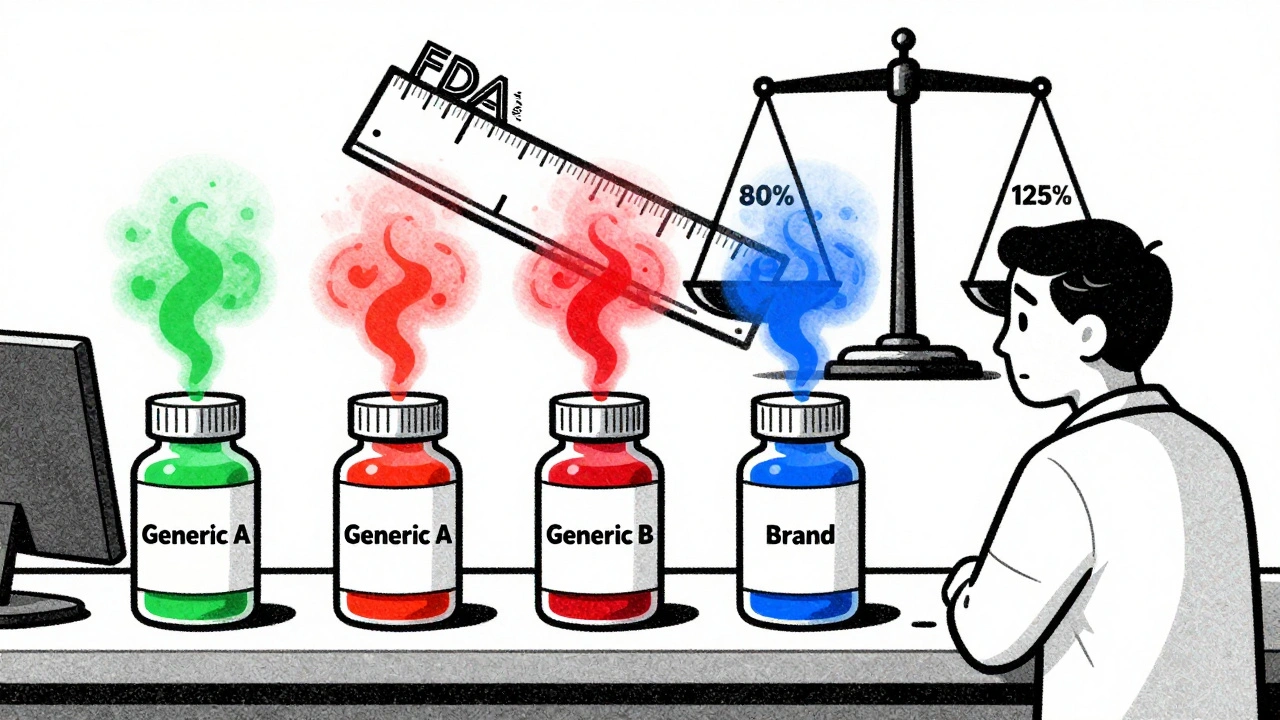

How the FDA Lets Two Generics Differ by 45%

The FDA requires generics to deliver between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s blood concentration. That’s a huge range. Imagine two different generic versions of the same drug. One delivers 82% of the active ingredient. The other delivers 123%. Both meet FDA standards. But together, they differ by 41%-more than enough to throw off someone who’s finely tuned on their medication.This isn’t theoretical. A 2021 analysis by Dr. Robert L. Lins explained that if one generic is at the bottom of the acceptable range and another is at the top, patients switching between them could experience a 45% swing in drug exposure without either product being out of compliance. For someone on warfarin, that could mean a dangerous clot or a life-threatening bleed. For someone on carbamazepine, it could mean a seizure they didn’t have before.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone reacts the same way. The people most likely to notice a difference are those on NTI medications, older adults, people with multiple chronic conditions, and those on complex drug regimens. A 2019 study from Harvard Medical School found that 28.4% of patients on multiple medications had adverse effects when switching between different generic manufacturers of the same drug. That’s almost 3 in 10 people.Some reactions aren’t even about the active ingredient. Take bupropion, the generic version of Wellbutrin. On Reddit’s r/pharmacy, hundreds of users reported severe headaches, anxiety, and brain zaps after switching to certain generic forms. Pharmacists confirmed this pattern: 68% of community pharmacists have seen patients have bad reactions when switched between different generic brands. And 41% say it happens frequently-more than five times a month.

Even allergies to inactive ingredients can cause real problems. Sodium metabisulfite, a preservative in some injectables and inhalers, triggers asthma attacks in 5-10% of asthmatic patients. If you’re switched to a generic version that contains it, and your old brand didn’t, you might not realize why you’re wheezing.

What the Data Says-And What It Doesn’t

It’s easy to dismiss these stories. After all, the FDA says 99.7% of generics pass bioequivalence tests. A 2024 study of 2.1 million patients found no overall increase in adverse events with generics across most drug classes. And yes, for drugs like metformin or statins, the differences are negligible. But that’s the problem: the data averages out the outliers.For the 4% of generic drugs labeled as “BX” by the FDA-meaning they may not be therapeutically equivalent for some patients-the system doesn’t flag them clearly. Patients don’t know. Doctors don’t always know. And pharmacies often switch them automatically unless told not to.

Thyroid patients are a prime example. A 2023 survey by ThyroidChange, a patient advocacy group, found that 72.6% of respondents had worse symptoms after switching from Synthroid to a generic. Over half needed a dose adjustment just to feel normal again. That’s not a fluke. That’s a pattern.

What You Can Do

If you’re on a medication with a narrow therapeutic index-or if you’ve ever felt worse after switching to a generic-here’s what to do:- Ask your doctor to write “Dispense as written” or “Do not substitute” on your prescription. This legally blocks the pharmacy from swapping your brand for a generic without approval.

- Know your drug class. Levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, carbamazepine, and cyclosporine are high-risk. If you’re on any of these, treat the generic like a different drug.

- Track your symptoms. Keep a simple log: date, medication name, dose, how you felt, any side effects. If you switch and feel off, you’ll have proof to show your doctor.

- Check inactive ingredients. The FDA has a public database of inactive ingredients. If you suspect an allergy or sensitivity, look up your pill’s exact formulation. You can ask your pharmacist for the manufacturer’s product insert.

- Stick with one generic manufacturer. If you’ve found a generic that works, don’t let the pharmacy switch you to another one. Ask for the same brand name every time.

Some pharmacies now have protocols to prevent automatic substitution for NTI drugs. CVS and Walgreens, for example, block substitutions for levothyroxine and warfarin unless the doctor approves it. But that’s not universal. You have to ask.

The Bigger Picture

The push for generics saves the U.S. healthcare system over $370 billion a year. That’s huge. But saving money shouldn’t come at the cost of patient safety. The FDA is starting to take notice. In 2024, they released new draft guidance for 23 high-risk drug classes, proposing stricter manufacturing standards. They’ve even approved an “authorized generic” of Synthroid-a version made by the original brand but sold under a generic label. It’s the same formula, just cheaper.And now, research is pointing toward personalized solutions. Pharmacogenomic testing can predict how your body will process certain drugs with 83.7% accuracy. In the future, your genetic profile might tell your doctor which generic version is safest for you.

For now, the system still treats all patients the same. But your body isn’t a statistic. If you’ve felt different after switching to a generic, you’re not imagining it. You’re not being difficult. You’re one of the people the system wasn’t designed to protect-and that’s something worth speaking up about.

Are generic medications always safe?

For most people and most medications, yes. Generic drugs are safe and effective for the vast majority of prescriptions-especially for drugs with wide therapeutic windows like metformin or atorvastatin. But for medications with a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin-even small changes in absorption can cause serious side effects. Safety isn’t universal; it depends on the drug and the individual.

Why do some generics make me feel worse?

It’s not usually the active ingredient-it’s the inactive ones. Fillers, dyes, coatings, and preservatives can change how quickly the drug dissolves or is absorbed. For people sensitive to these changes, especially those on NTI drugs, even a 10% difference in blood concentration can cause fatigue, mood swings, headaches, or seizures. Some people also have allergies to ingredients like sodium metabisulfite, which may be in one generic but not another.

Can I ask my pharmacist not to switch my generic?

Yes, absolutely. You have the right to request that your prescription be filled with a specific brand or generic manufacturer. You can also ask your doctor to write “Dispense as written” or “Do not substitute” on your prescription. This legally prevents the pharmacy from switching it without your doctor’s approval. Many pharmacists will honor this request, especially for high-risk medications.

What should I do if I think my generic is causing side effects?

First, don’t stop taking your medication. Contact your doctor right away. Keep a symptom log-note when you switched, what you were taking before, and what symptoms started or changed. For NTI drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, your doctor may need to check blood levels (TSH or INR) within days or weeks of the switch. If the issue is confirmed, ask for your previous formulation to be reinstated.

Is there a way to find out which generic manufacturer I’m getting?

Yes. The name of the manufacturer is usually printed on the pill bottle or the packaging. You can also ask your pharmacist for the manufacturer’s name and look up the inactive ingredients in the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database. If you’ve had a bad reaction to one brand, keep track of the name so you can avoid it in the future.

Are authorized generics better than regular generics?

Authorized generics are made by the original brand-name manufacturer but sold under a generic label. They contain the exact same active and inactive ingredients as the brand version. For patients who’ve had bad reactions to other generics, an authorized generic can be a safer, lower-cost alternative. For example, the authorized generic of Synthroid is identical to the brand, just cheaper. It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s the closest thing to consistency.

Comments

John Webber

so like... generics are fine for most stuff but if you're on thyroid meds or blood thinners? yeah you better stick with the same one. my aunt went from Synthroid to some generic and started having heart palpitations. doctor said her TSH went nuts. she had to switch back. no joke.

December 2, 2025 AT 10:11

Shubham Pandey

generic = cheaper. that's it. stop overthinking.

December 3, 2025 AT 20:29

Elizabeth Farrell

I just want to say how important it is to listen to your body. I’ve been on levothyroxine for over a decade and switched generics three times. The first time I didn’t notice anything. The second time, I felt like I was dragging through mud for weeks-depressed, tired, foggy brain. I kept a journal, showed my doctor, and asked for the original generic manufacturer. It made all the difference. You’re not crazy if you feel different. Your body is telling you something. Trust it. And don’t be afraid to ask your pharmacist for the brand name. They’re there to help, not just fill prescriptions.

December 5, 2025 AT 17:54

John Biesecker

the FDA says 99.7% are fine... but what about the 0.3%? 😅

we’re not stats. we’re humans with weird bodies. if you feel off after a switch? it’s real. i switched generics for my seizure med and had a mini-seizure. not funny. not a coincidence. the system treats us like robots. we’re not.

December 7, 2025 AT 12:20

Genesis Rubi

why are americans so weak? in my country we take whatever generic they give us and don't cry about it. if your body can't handle a pill, maybe you're just lazy. also, why do we pay for brand names when the science says they're the same? capitalism is broken.

December 7, 2025 AT 16:27

Doug Hawk

the real issue here is bioequivalence margins. 80-125% is a massive window. for NTI drugs that's not just sloppy, it's dangerous. and the FDA doesn't require manufacturers to disclose which excipients they use in a way patients can easily cross-reference. there's no centralized registry of inactive ingredients across generics. if you're on warfarin or phenytoin, you're playing Russian roulette with your pill bottle. and nobody's talking about the fact that pharmacists often switch without telling you. it's not transparency. it's negligence.

December 9, 2025 AT 09:21

John Morrow

let’s be honest: most people who complain about generics are either hypochondriacs or people who don’t understand pharmacokinetics. the FDA doesn’t approve drugs based on anecdotes. the data is clear: no significant increase in adverse events across millions of patients. if you’re one of the rare outliers, sure, get tested. but don’t turn a statistical blip into a moral crusade. you’re not special. you’re just statistically improbable.

December 10, 2025 AT 17:38

Saurabh Tiwari

cool post. i'm on a generic for my epilepsy med and never had issues. but i know someone who had seizures after switching. maybe it's not about right or wrong... just that some people are more sensitive. i think we need better labeling on bottles. like a little icon or code for NTI drugs. easy to read. no jargon. just info.

December 12, 2025 AT 16:33

Michael Campbell

they're lying. the big pharma cartel controls the generics too. same factories. same owners. they just rebrand it. you think they care if you have a seizure? no. they make more money off the switch. watch the stock prices after a new generic hits. it's all rigged.

December 13, 2025 AT 12:22

Sandi Allen

THIS. Exactly this. The FDA is a puppet of Big Pharma. They let generics vary by 45%? That’s not science-that’s corporate greed dressed up as regulation. And don’t get me started on how pharmacies auto-switch without consent. It’s medical malpractice. I’ve seen patients on warfarin with INRs off the charts after a switch. And the doctors? They blame the patient. "You didn’t take it right." No. You gave me a different drug. And the system protects the manufacturers, not the people. Wake up. This isn’t about cost savings. It’s about control. And we’re the pawns.

December 13, 2025 AT 19:19