Renal Dosing Calculator: CrCl & Antibiotic Adjustment

Calculate Creatinine Clearance (CrCl)

Use the Cockcroft-Gault equation to determine kidney function for proper antibiotic dosing.

Your Creatinine Clearance Results

Kidney Function Classification

Dosing Recommendations for Key Antibiotics

Standard: 1.5-3 g IV every 6h

CrCl 15-29 mL/min: 2 g every 12h

CrCl <15 mL/min: 2 g every 24h

Standard: 1-2 g every 8h

CrCl <10 mL/min: 500 mg-1 g every 12-24h

Standard: 500 mg every 12h

CrCl 10-30 mL/min: 250 mg every 12h

Standard: 25-30 mg/kg loading dose

Maintenance: 15 mg/kg every 48-72h

Standard: 500 mg every 12h

CrCl <30 mL/min: 500 mg every 24h

Standard: 3.375 g IV every 8h

Augmented renal clearance: 4.5 g every 4h

When a patient has kidney disease, giving them the same antibiotic dose as someone with healthy kidneys isn't just risky-it can be deadly. Antibiotics don't just disappear after they do their job. Many are cleared by the kidneys. If those kidneys aren't working right, the drugs build up. And that buildup doesn't just cause nausea or dizziness. It can lead to seizures, permanent nerve damage, or even death. The question isn't whether to adjust the dose-it's how to do it right, every time.

Why Renal Dosing Isn't Optional

Chronic kidney disease affects about 15% of adults in the U.S. That’s 37 million people. Globally, it’s over 850 million. Many of these patients end up in the hospital with infections-pneumonia, UTIs, skin infections. And most of them need antibiotics. But here’s the problem: if you give them a standard dose, you're essentially overdosing them. Studies show that incorrect dosing in kidney disease increases death risk by nearly 30% in pneumonia patients and over 20% in those with abdominal or urinary infections. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening in hospitals right now.

It’s not just about killing the infection. It’s about keeping the patient alive long enough to recover. Too little antibiotic, and the infection doesn’t budge. Too much, and the patient’s nervous system, kidneys, or ears get damaged. The goal isn’t to give less-it’s to give the right amount.

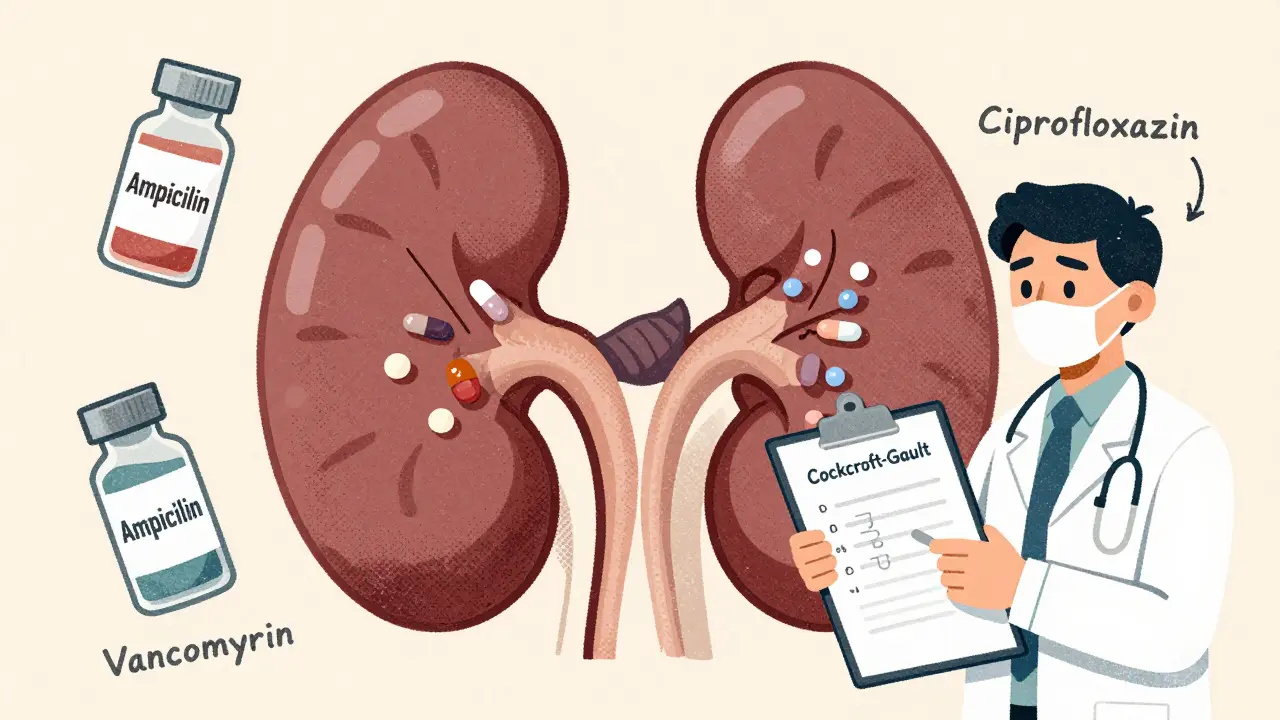

How Doctors Measure Kidney Function: CrCl, Not Just Creatinine

Many doctors look at serum creatinine alone and assume they know what’s going on. That’s a mistake. Creatinine levels don’t tell the full story. A 75-year-old woman with a creatinine of 1.2 might have worse kidney function than a 30-year-old athlete with a creatinine of 1.4. Why? Because muscle mass changes with age, sex, and body size.

The gold standard for dosing is creatinine clearance (CrCl), estimated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation. It uses age, weight, sex, and serum creatinine. The formula looks complicated, but it’s simple in practice:

CrCl = [(140 − age) × weight (kg)] / [72 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)] × 0.85 (if female)

For example, a 68-year-old woman weighing 60 kg with a creatinine of 1.5:

[(140 − 68) × 60] / [72 × 1.5] × 0.85 = (72 × 60) / 108 × 0.85 = 4320 / 108 × 0.85 = 40 × 0.85 = 34 mL/min

That’s moderate kidney impairment. Now, the right dose for ampicillin/sulbactam changes from 2 g every 6 hours to 2 g every 12 hours. Get this wrong, and you’re either underdosing or poisoning the patient.

Which Antibiotics Need Adjustment? The Big Six

Not all antibiotics are created equal. About 60% of commonly used ones require dose changes in kidney disease. But only 25% have a narrow therapeutic window-meaning the difference between helping and harming is razor-thin. Here are the top six that demand attention:

- Ampicillin/sulbactam: Standard is 1.5-3 g IV every 6 hours. For CrCl 15-29 mL/min, drop to 2 g every 12 hours. For CrCl under 15, use 2 g every 24 hours. No loading dose needed here.

- Cefazolin: Usually 1-2 g every 8 hours. But if CrCl is under 10 mL/min, use 500 mg to 1 g every 12-24 hours. This one has a wide safety margin, so underdosing is more dangerous than overdosing in acute cases.

- Ciprofloxacin: Oral dosing errors are shockingly common. Standard is 500 mg every 12 hours. For CrCl 10-30 mL/min, cut it to 250 mg every 12 hours. Many patients get the full dose, leading to central nervous system toxicity-seizures, hallucinations.

- Vancomycin: This one’s tricky. You need a loading dose (25-30 mg/kg) even in kidney failure to get levels up fast. Then, maintenance doses drop to 15 mg/kg every 48-72 hours. Therapeutic drug monitoring is mandatory.

- Clarithromycin: Standard is 500 mg every 12 hours. For CrCl under 30 mL/min, switch to 500 mg every 24 hours. Some guidelines say no adjustment below 50 mL/min-this inconsistency causes real confusion.

- Piperacillin/tazobactam: For patients with augmented renal clearance (CrCl >130 mL/min), like trauma or sepsis patients, you may need 4.5 g every 4 hours. Most guidelines miss this entirely.

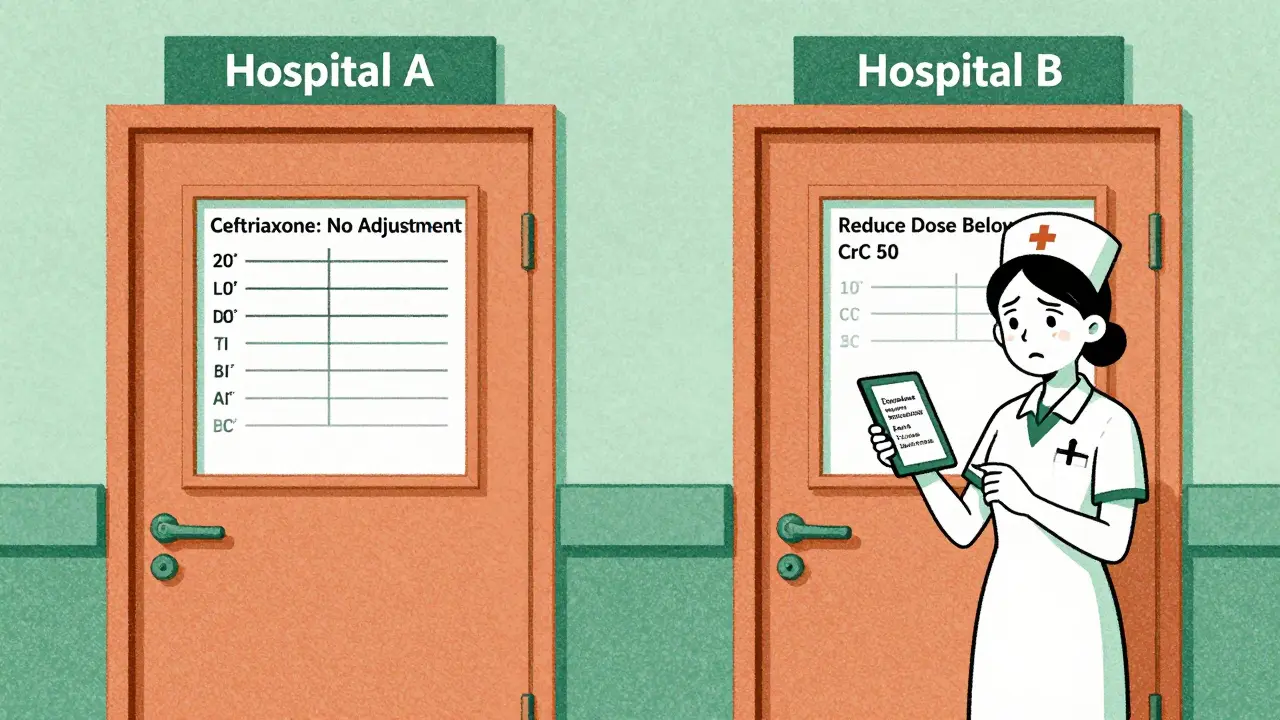

The Guideline Mess: Why Two Hospitals Might Give Different Doses

Here’s where things get messy. Three major sources-KDIGO, UNMC, and Northwestern Medicine-all have different recommendations. And hospitals pick one. Sometimes, they pick the wrong one.

Take ceftriaxone. UNMC says: no adjustment needed at any CrCl level. Northwestern Medicine says the same. But a nurse at a rural hospital might pull up an outdated institutional guideline that says to reduce the dose for CrCl under 50. The patient gets 500 mg instead of 1 g. The infection doesn’t clear. Days later, they’re back in the ER.

Or consider clarithromycin. UNMC reduces the dose only when CrCl drops below 30. Northwestern says reduce if CrCl is below 50. That’s a 20 mL/min difference. A patient with CrCl at 40 might get the wrong dose depending on which hospital they walk into.

And then there’s CRRT (continuous renal replacement therapy). Only Northwestern Medicine’s June 2025 guidelines include specific dosing for this. Most hospitals don’t even have protocols. If a patient is on dialysis and you give them cefazolin at the standard dose? They’ll likely get toxic levels.

One survey found that 41% of hospital pharmacists struggle because guidelines conflict. That’s not a gap in knowledge-it’s a gap in standardization.

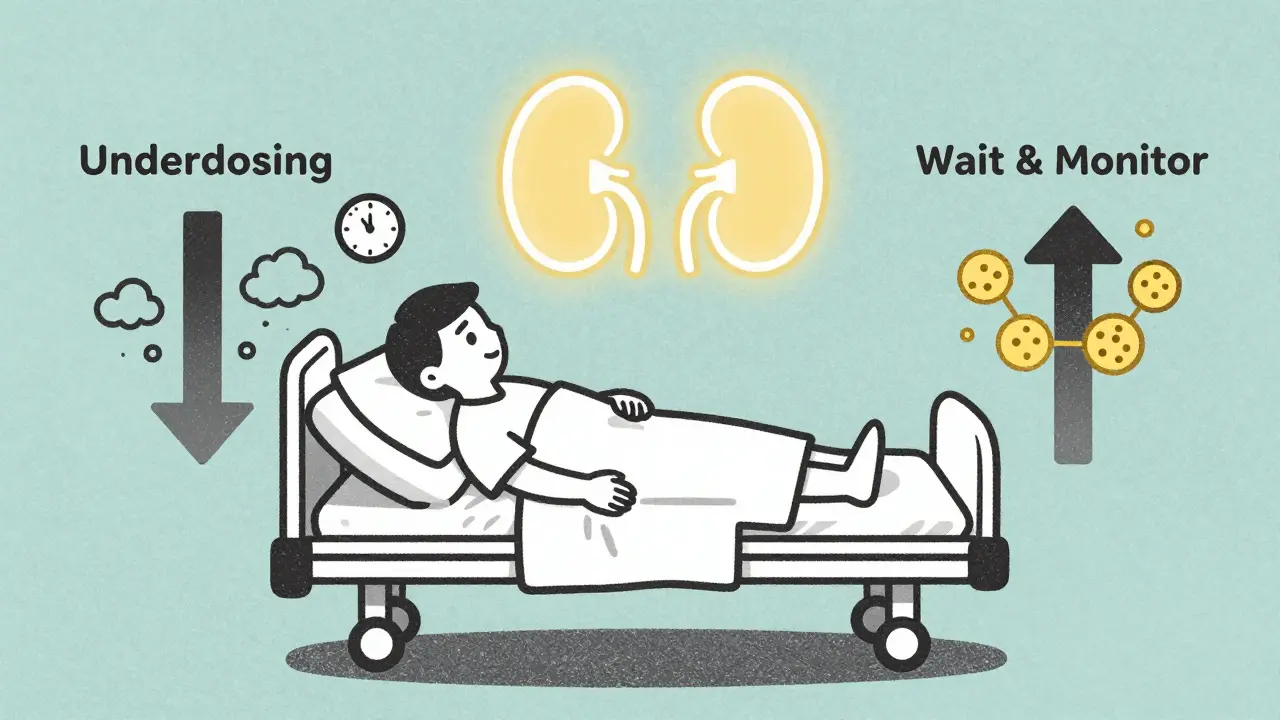

Acute vs. Chronic: The Biggest Blind Spot

Most dosing guidelines were written for patients with stable, long-term kidney disease. But what about acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Over half of AKI cases resolve in 48 hours. Yet, doctors often reduce antibiotic doses immediately, assuming the kidneys are permanently damaged. That’s a mistake. In AKI, the kidneys are still working-just not efficiently. Underdosing here means treatment failure. A 2019 study showed underdosing increases treatment failure risk by 34% in AKI patients.

On the flip side, if the kidneys start recovering fast and you don’t increase the dose? The antibiotic levels crash. The infection comes roaring back. This is why some experts argue: delay dose reduction in AKI. Hold off for 48 hours. Monitor. Then adjust. Don’t assume.

And here’s the kicker: the FDA now requires new antibiotics to be tested in patients with AKI. The old model-testing only in stable CKD-is outdated. Real-world patients aren’t stable. They’re sick, fluctuating, and recovering.

How to Get It Right: Tools and Systems That Work

There’s no magic bullet. But there are systems that reduce errors by over 40%.

- Electronic Health Record (EHR) Alerts: 89% of U.S. hospitals now have alerts that pop up when a drug is ordered for a patient with low CrCl. These are lifesavers.

- Pharmacist-Led Dose Adjustment: Hospitals with clinical pharmacists reviewing all antibiotic orders in kidney disease patients see a 37% drop in adverse events. Pharmacists catch what doctors miss.

- Institutional Protocols: 72% of academic centers standardize on KDIGO guidelines. That reduces confusion. If everyone uses the same source, errors drop.

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): For drugs like vancomycin and linezolid, checking blood levels before the third dose prevents toxicity. By 2027, 65% of academic hospitals will use this routinely.

- AI Dosing Tools: Pilot programs at 17 teaching hospitals now use AI to predict optimal dosing based on CrCl, weight, age, and even urinary biomarkers. These tools learn from real outcomes-not just guidelines.

One hospital in Brisbane switched to pharmacist-led dosing for all renal patients. Within six months, antibiotic-related readmissions dropped by 51%.

The Bottom Line: What You Need to Remember

- Don’t rely on serum creatinine alone. Calculate CrCl using Cockcroft-Gault.

- Know which antibiotics need adjustment-and which don’t. Ceftriaxone? Usually no change. Ciprofloxacin? Always adjust.

- Don’t automatically reduce doses in acute kidney injury. Wait 48 hours. Reassess.

- For drugs like vancomycin, give the loading dose-even if kidneys are failing.

- Use institutional protocols or EHR alerts. Don’t rely on memory.

- When in doubt, consult a pharmacist. They’re trained for this.

Antibiotics in kidney disease aren’t about being careful. They’re about being precise. A few milligrams too much or too little can change survival. And that precision starts with one thing: knowing how to calculate CrCl-and never guessing.

How do I calculate creatinine clearance (CrCl) for antibiotic dosing?

Use the Cockcroft-Gault equation: CrCl = [(140 − age) × weight (kg)] / [72 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)] × 0.85 if female. For example, a 70-year-old man weighing 70 kg with a creatinine of 1.8: [(140−70) × 70] / [72 × 1.8] = (70 × 70) / 129.6 = 4900 / 129.6 ≈ 37.8 mL/min. This puts him in moderate renal impairment. Always use actual body weight unless the patient is obese-then use ideal body weight.

Do all antibiotics need dose adjustment in kidney disease?

No. About 60% of commonly used antibiotics require adjustment. Drugs like ceftriaxone, azithromycin, and linezolid are mostly cleared by the liver and don’t need changes. But antibiotics like vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, and gentamicin are cleared by the kidneys and must be adjusted. Always check the latest guidelines-some drugs have changed.

Why is CrCl used instead of eGFR for dosing?

eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate) is great for tracking long-term kidney health. But for dosing antibiotics, CrCl is more accurate because it accounts for body weight and muscle mass-key factors in how drugs are cleared. The MDRD and CKD-EPI equations used for eGFR were designed for population-level estimates, not individual drug dosing. CrCl remains the gold standard in clinical pharmacology.

What should I do if a patient has acute kidney injury (AKI)?

Don’t reduce the dose immediately. AKI often reverses within 48 hours. Give the full standard dose initially unless the patient is severely ill or on dialysis. Reassess kidney function daily. If CrCl improves, increase the dose. If it worsens, reduce it. Delaying adjustment prevents treatment failure, which is more dangerous than temporary toxicity.

Can I use the same antibiotic dose for dialysis patients?

No. Dialysis removes some antibiotics but not others. Vancomycin is removed heavily-you’ll need a dose after each session. Cefazolin is only partially removed, so you might give 75% of the usual dose post-dialysis. Always check specific guidelines for each drug and dialysis type (HD, CRRT, PD). Many hospitals have dialysis-specific protocols.

What’s the biggest mistake clinicians make with renal dosing?

Assuming that ‘less is always safer.’ Many clinicians reduce doses out of fear of toxicity, even when the drug has a wide safety margin-like cefazolin. In reality, underdosing in kidney disease often leads to treatment failure, longer hospital stays, and higher death rates. The goal isn’t to minimize risk-it’s to optimize exposure. Sometimes, that means giving more than they think.

Comments

Irish Council

So we're just supposed to trust some math equation from 1976 while patients die from underdosing or overdosing

February 18, 2026 AT 10:10

Jayanta Boruah

The Cockcroft-Gault equation remains the gold standard precisely because it integrates weight, age, and sex into a clinically actionable metric. eGFR equations, while statistically robust for population epidemiology, lack the physiological granularity required for pharmacokinetic precision. The FDA's recent mandate for AKI-inclusive trials underscores the inadequacy of legacy models. Clinical decision-making demands dynamic, individualized parameters-not population averages masked as guidelines.

February 19, 2026 AT 13:28

Benjamin Fox

USA rules. We got the best protocols. Why are we even talking about other countries' guidelines? 🇺🇸

February 21, 2026 AT 01:28

Tommy Chapman

Anyone who doesn't use EHR alerts is just putting patients at risk on purpose. This isn't rocket science. If you're still doing this by memory you're a danger to public health. 🤦♂️

February 21, 2026 AT 22:09

Robin bremer

so like... if ur kidney is broke u just gotta chill with the antibiotics? lol i always thought more was better 😅

February 23, 2026 AT 21:35

Hariom Sharma

This is why I love medicine-every patient is a puzzle. CrCl isn’t just a number, it’s a story. A 70-year-old woman with low muscle mass isn’t the same as a 30-year-old athlete with high creatinine. When we stop guessing and start calculating, we don’t just treat-we honor the person. Keep pushing for precision. We’re getting better. 💪

February 25, 2026 AT 13:04

Jana Eiffel

The fundamental ethical dilemma in renal dosing lies not in pharmacokinetic algorithms, but in the epistemological arrogance of clinical protocols. We have constructed a system wherein institutional guidelines-often arbitrary, inconsistently updated, and regionally fragmented-replace individualized clinical judgment. The very notion that a single equation, derived from 1970s cohort data, can govern the dosing of life-saving agents across diverse populations of age, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidity is not merely outdated-it is ontologically flawed. We must replace algorithmic dogma with dynamic, biomarker-guided, real-time therapeutic monitoring. The patient is not a variable in a spreadsheet. They are a biological narrative unfolding in real time.

February 26, 2026 AT 15:01

Jonathan Rutter

Let me tell you something. I've seen this too many times. A patient gets cefazolin at the full dose because the resident didn't check CrCl. They end up with encephalopathy. Not because the drug was toxic. Because it was underdosed and the infection spread. Then the family sues. And the hospital blames the pharmacist. But the pharmacist didn't even see the order until after the fact. You want to save lives? Put pharmacists at the front of the line. Not as an afterthought. As the gatekeeper. Every. Single. Time. No exceptions. No 'maybe'. If you're not doing this, you're not practicing medicine-you're gambling.

February 28, 2026 AT 08:20