When a generic drug hits the market, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know for sure? Traditional measures like Cmax and total AUC used to be enough. Today, they’re often not. That’s where partial AUC comes in - a more precise tool used to make sure generic drugs don’t just look similar on paper, but behave the same in your body.

Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short

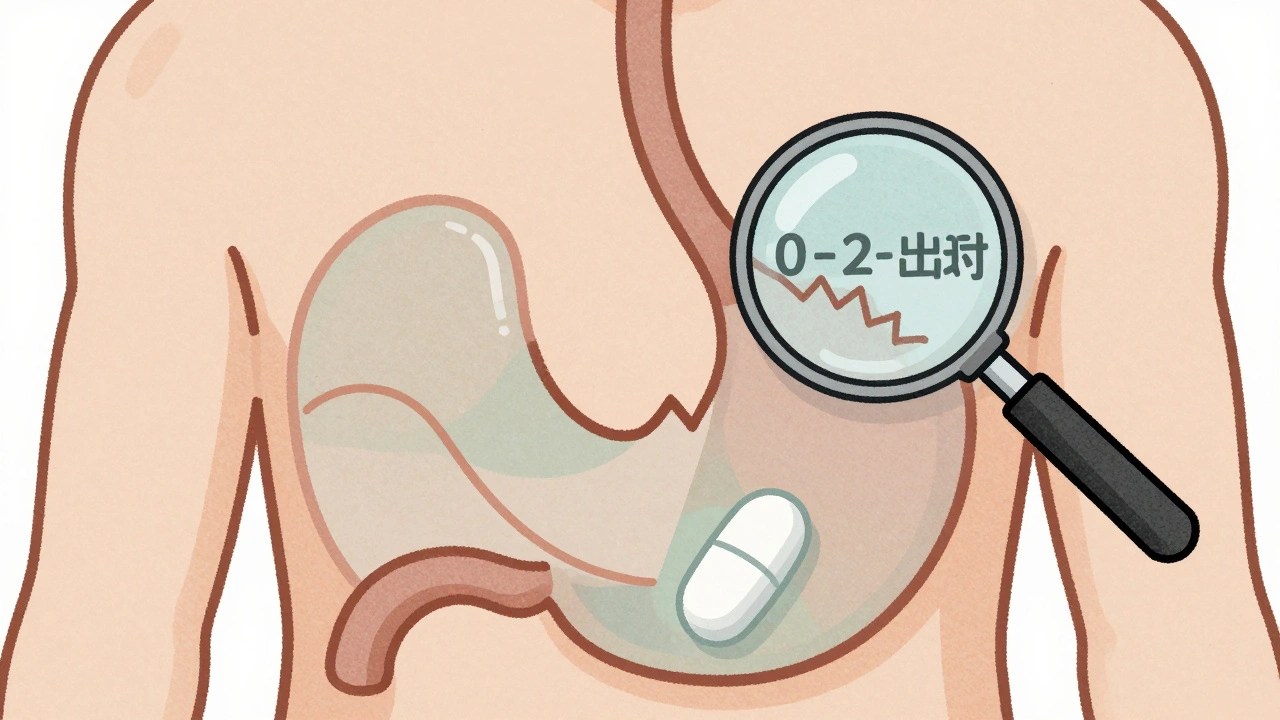

For years, bioequivalence was judged using two numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration of drug in your blood) and total AUC (the total amount of drug your body absorbs over time). These worked fine for simple, fast-acting pills. But they started failing when drugs got more complex - like extended-release painkillers, abuse-deterrent opioids, or combination formulations that release medicine in stages. Here’s the problem: two drugs might have identical Cmax and total AUC, but one releases its dose slowly over 12 hours, while the other spikes quickly and fades fast. For a patient, that difference matters. A fast spike could cause side effects. A slow release might not control pain when it’s needed most. Traditional metrics couldn’t catch that. That’s why regulators turned to partial AUC - a way to zoom in on specific parts of the drug’s journey through your body. Instead of looking at the whole curve, you focus only on the time window that matters clinically. For example, the first 1-2 hours after dosing, when absorption is happening. Or the period when drug levels are above 50% of peak concentration.What Exactly Is Partial AUC?

Partial AUC, or pAUC, is the area under the drug concentration-time curve - but only over a defined time interval. Think of it like taking a magnifying glass to a specific section of a graph instead of judging the whole picture. The FDA and EMA don’t use one fixed definition. The time window depends on the drug. Common approaches include:- From time zero to the Tmax (time to peak concentration) of the reference product

- From time zero until drug concentration drops below 50% of Cmax

- From time zero until the concentration exceeds a clinically relevant threshold

How It’s Calculated and Approved

Calculating pAUC isn’t simple. You need detailed blood samples over time, and you need to know exactly when to start and stop measuring. Statistical methods like the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller approach are used to build 90% confidence intervals for the test-to-reference ratio. The acceptance criteria are the same as for total AUC: the 90% confidence interval of the ratio must fall between 80% and 125%. But here’s the catch - pAUC often has higher variability. That means you might need more participants in your study. A 2014 study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generic drugs that passed traditional bioequivalence tests failed when pAUC was added. When both fasting and fed conditions were tested, failure rates jumped to 40%. That’s not a flaw in the system - it’s proof that pAUC is doing its job: catching hidden differences. The FDA now includes pAUC in over 127 product-specific guidances as of 2023. That’s up from just a handful in 2015. These guidances are the rulebook for generic drug makers. If your drug is on the list, you must include pAUC in your submission - or your application gets rejected.

Real-World Impact: Cases That Changed the Game

In 2021, a case presented at the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists showed how pAUC prevented a dangerous generic from reaching patients. The test and reference products had nearly identical Cmax and total AUC. But when researchers looked at the first 2 hours after dosing - the pAUC window - they found a 22% difference in early exposure. That difference meant the generic could cause sudden spikes in blood levels, increasing overdose risk. The drug was pulled before approval. Another example: a Teva Pharmaceuticals team working on an extended-release opioid generic. Their initial study used 36 subjects. After adding pAUC requirements, they had to increase the sample size to 50. That added $350,000 to development costs - but it avoided a potential clinical failure down the line. On the flip side, 17 ANDA applications were rejected in 2022 just because the pAUC time window was poorly defined. Some companies used their own cutoffs without regulatory backing. Others picked time points that didn’t align with the reference product’s Tmax. These aren’t small errors. They’re fundamental misunderstandings of how pAUC works.Who Uses It and Why It’s Growing

pAUC isn’t used for every drug. It’s reserved for complex formulations:- Extended-release tablets and capsules

- Abuse-deterrent opioids

- Combination IR/ER products

- CNS drugs (like epilepsy or Parkinson’s meds)

- Cardiovascular agents with narrow therapeutic windows

Challenges and Controversies

Despite its value, pAUC isn’t perfect. The biggest issue? Lack of standardization. Different product-specific guidances give different instructions. Some say to use reference Tmax. Others say to use 50% of Cmax. A few don’t specify at all. A 2022 survey found only 42% of FDA guidances clearly defined the time interval. This creates uncertainty. Generic developers waste months guessing what the FDA wants. One Reddit user in r/pharmacometrics called it “a moving target.” There’s also a cost problem. Higher variability means larger studies. A 2020 commentary in the Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics estimated sample sizes may need to increase by 25-40%. That’s expensive. And then there’s the learning curve. Biostatisticians need 3-6 months of training to use pAUC correctly. Tools like Phoenix WinNonlin and NONMEM aren’t easy. Many companies hire consultants just to run these analyses.What’s Next for Partial AUC?

The FDA is trying to fix the inconsistency. In early 2023, they launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC time windows based on reference product data. The goal? Reduce guesswork. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC - nearly double today’s rate. The EMA is expanding too. Their 2021 reflection paper added 15 new drug categories requiring pAUC. The long-term trend is clear: regulators are moving away from one-size-fits-all metrics. They want precision. They want to match drug behavior to real patient outcomes. pAUC is the tool that makes that possible.Final Thoughts

Partial AUC isn’t just another statistic. It’s a shift in how we think about generic drugs. It’s not enough for a drug to have the same total exposure. It needs to release at the right time, in the right way. For patients with chronic conditions, that difference can mean the difference between control and crisis. If you’re developing a generic drug, ignoring pAUC is risky. If you’re a patient, knowing it exists means you can trust that your medication was held to a higher standard. The science is sound. The data backs it. The regulators are doubling down. The question isn’t whether pAUC matters - it’s whether you’re ready for it.What is partial AUC in bioequivalence?

Partial AUC (pAUC) measures drug exposure over a specific time window during absorption, rather than the entire concentration-time curve. It helps regulators compare how quickly and consistently a generic drug releases its active ingredient compared to the brand-name version, especially for complex formulations like extended-release or abuse-deterrent products.

Why is pAUC better than total AUC for some drugs?

Total AUC only tells you how much drug was absorbed overall. It doesn’t show when or how fast it was absorbed. For drugs that need rapid onset (like painkillers) or steady release (like blood pressure meds), timing matters. pAUC focuses on the critical window - like the first 2 hours - where differences in release rates can affect safety or effectiveness.

Which regulatory agencies require pAUC?

Both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) require pAUC for certain complex drug products. The FDA lists over 127 specific products in its product-specific guidances that mandate pAUC analysis. The EMA began including it in 2013 and has since expanded its use to 27 categories of modified-release formulations.

How is the time window for pAUC chosen?

The time window should be based on a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic effect - not arbitrary numbers. Common methods include using the reference product’s Tmax, measuring until drug concentration drops to 50% of Cmax, or focusing on the period when concentrations exceed a therapeutic threshold. The FDA recommends linking the window to observable patient outcomes like pain relief or seizure control.

Do I need more subjects for a pAUC study?

Yes, often. pAUC tends to have higher variability than total AUC or Cmax, meaning you may need 25-40% more participants to achieve statistical power. A study that used 36 subjects for traditional metrics might need 50 or more when pAUC is included. This increases costs but reduces the risk of approving a product that fails in real-world use.

What happens if a generic drug fails pAUC testing?

If the 90% confidence interval of the test-to-reference ratio falls outside the 80-125% range for pAUC, the application is rejected. In 2022, 17 ANDA submissions were denied due to incorrect pAUC time window selection. This prevents potentially unsafe or ineffective generics from reaching patients.

Comments

Aidan Stacey

So let me get this straight - we’re now measuring drug absorption like we’re analyzing a wine’s bouquet? 🍷

First 2 hours? 50% of Cmax? This isn’t science anymore - it’s performance art.

But honestly? I’m here for it. If this stops some lazy generic from killing someone because it spiked too fast, then yes, let’s over-analyze the curve.

My uncle took a bad generic for his seizures - ended up in the ER. This is the kind of detail that saves lives, not just satisfies regulators.

Also, the fact that 40% failed under fed/fasting combo? That’s wild. We’ve been letting people take meds like they’re candy for decades.

Time to stop pretending ‘same pill, same effect’ is good enough.

Also - who’s gonna pay for these 50-person studies? Small companies are gonna get crushed.

But hey, better safe than sorry. I’ll take a pricier pill that doesn’t turn me into a zombie at 3am.

December 11, 2025 AT 21:36

Nikki Smellie

Have you ever wondered why the FDA suddenly cares about ‘partial AUC’ after 2015? Coincidence? Or did Big Pharma lobby for this to eliminate small generic competitors?

Think about it: they control the reference products. They control the ‘clinically relevant windows.’

What if the time window is chosen to favor the brand? What if the ‘therapeutic threshold’ is arbitrarily set to make generics fail?

And who funds the validation studies? The same labs that work for the big guys.

It’s not about safety - it’s about market control.

They call it ‘precision medicine.’ I call it corporate gatekeeping.

And don’t get me started on the machine learning pilot - AI trained on proprietary data? That’s not innovation. That’s algorithmic bias.

Wake up. This isn’t science. It’s a financial weapon.

And we’re all paying for it - in higher prices and fewer options.

They want you to believe this is progress. It’s not. It’s consolidation.

And the EMA? Same playbook. Global pharma doesn’t care about patients. They care about margins.

Read between the lines. This isn’t about safety. It’s about control.

And the next thing you know, your blood pressure med will be patented again under a ‘new formulation’ - with a new pAUC window.

They’re not fixing the system. They’re rigging it.

December 13, 2025 AT 02:52

Neelam Kumari

Wow. So now we need PhDs just to take a pill? 😒

Let me guess - next they’ll require a blood test before you can buy ibuprofen.

And you’re proud of this? A 22% difference in early exposure? That’s what you’re screaming about?

Meanwhile, in India, people get life-saving generics for $0.10 a pill.

But here? You need a $350k study just to prove it doesn’t spike too fast?

Who’s the real villain here? The generic makers? Or the overpaid regulators who turned bioequivalence into a 10-course tasting menu?

Also - 17 applications rejected because the time window was ‘poorly defined’?

That’s not a technical issue. That’s a bureaucratic nightmare.

Stop pretending this is science. It’s a money-printing machine for CROs and consultants.

And you wonder why healthcare is broken?

Here’s your answer.

December 14, 2025 AT 16:07

Queenie Chan

Imagine your drug is a symphony - total AUC is just counting how many notes were played.

Partial AUC? That’s listening to the crescendo in the second movement - the part that makes you cry.

For pain meds? That’s the first 90 minutes when the fire in your spine starts to dim.

For epilepsy? That’s the 4-hour window when your brain doesn’t short-circuit.

It’s not math. It’s rhythm.

And if your generic is off-beat? You’re not just ‘similar’ - you’re dangerous.

I used to think this was overkill.

Then I saw a friend’s kid go into status epilepticus because their ‘bioequivalent’ seizure med released too slow.

Turns out, the ‘total AUC’ was perfect.

The pAUC? Off by 30%.

So yeah - I’m all in.

Let’s make the regulators do the hard work.

Because when your life depends on timing, you don’t want ‘close enough.’

You want precision.

Even if it costs more.

Even if it’s messy.

Even if it takes 50 people instead of 36.

Some things are worth the fuss.

December 14, 2025 AT 23:43

Paul Dixon

Man, I didn’t even know this was a thing until today.

But honestly? This makes total sense.

I take an extended-release pain med - used to get those 3am crashes where I’d wake up screaming.

Switched to a generic and it was a nightmare.

Turns out, the brand kept me at 60% of peak for 8 hours.

The generic? Dropped to 30% by hour 5.

My doc had no idea why I was in pain at night.

Turns out - they never measured the 6-12 hour window.

So yeah, pAUC isn’t fancy jargon.

It’s just… common sense.

Let’s stop pretending all pills are created equal.

Some of us are living with this stuff daily.

And if this keeps someone from having a bad night? Worth every penny.

December 16, 2025 AT 08:36

Vivian Amadi

Let’s be real: this is just another way for the FDA to look like they’re doing something while letting Big Pharma off the hook.

They’re not cracking down on the real offenders - they’re making small companies fail.

And don’t tell me ‘safety’ - the brand-name drugs have the same release profiles.

Why isn’t the FDA forcing the originators to change their formulas?

Because they’re the ones writing the guidances.

It’s a rigged game.

And now we’re all supposed to cheer because some statistic changed?

Pathetic.

Next they’ll require a notarized affidavit from your liver before you can take aspirin.

Meanwhile, the real problem - drug pricing - is ignored.

Typical.

December 16, 2025 AT 20:08

Courtney Blake

So now we need to measure every single second of drug release like it’s a hostage negotiation?

And you’re proud of this? 😒

Meanwhile, people are dying from opioid overdoses because they can’t afford the brand.

But hey - let’s make the generics so expensive and hard to approve that nobody can make them.

That’s the real goal, isn’t it?

Keep the prices high.

Keep the competition out.

Call it ‘precision.’

I call it corporate murder.

And the ‘22% difference’? That’s a number pulled out of a hat.

Who says 2 hours is the magic window?

Some consultant in a lab coat.

Not a patient.

Not a doctor.

Just a guy with a spreadsheet.

And now you’re all acting like this is progress?

It’s not.

It’s control.

And you’re all just applauding.

December 17, 2025 AT 15:06

Lisa Stringfellow

So… this is why my generic blood pressure med stopped working after 6 months?

I thought I was just getting old.

Turns out - maybe the pAUC window wasn’t measured right.

And now I’m stuck paying $120 a month for the brand.

Thanks, regulators.

At least now I know why my insurance won’t cover the cheaper version.

It’s not that I’m ‘non-compliant’.

It’s that the generic failed a test I didn’t even know existed.

And I’m supposed to be grateful?

For what? For being a guinea pig?

At least tell us which time windows matter.

Don’t make us guess.

And don’t pretend this is about safety.

It’s about money.

And we’re the ones paying.

December 18, 2025 AT 15:42

Kristi Pope

This is beautiful.

Not because it’s perfect - but because it’s honest.

For years, we treated drugs like they were Lego bricks - same shape, same color, same outcome.

But bodies aren’t Lego.

They’re living systems.

And timing? It’s everything.

That 22% difference in early exposure? That’s not a statistic.

That’s someone’s panic attack.

That’s someone’s seizure.

That’s someone’s dad not waking up for breakfast.

So yes - let’s spend the extra money.

Let’s run the bigger studies.

Let’s make the CROs earn their fees.

Because the cost of failure? It’s not in dollars.

It’s in breaths.

And I’d rather pay more for a pill that doesn’t kill me.

Thank you for writing this.

It’s the kind of clarity we need.

Not more jargon.

More humanity.

December 20, 2025 AT 03:44

Aman deep

Wow. I read this while waiting for my chai at the clinic.

My mom takes an ER blood pressure med.

She had a stroke last year - doc said it was because her generic didn’t hold the pressure steady.

We never knew why.

Now I get it.

It’s not about the total amount.

It’s about the rhythm.

Like a heartbeat.

One pill too fast - boom.

One pill too slow - crash.

And the fact that 40% failed under fed/fasting? That’s wild.

My mom takes hers with breakfast.

What if the generic was tested fasting?

She’s not a lab rat.

She’s a person.

So yeah.

I’m glad someone’s finally paying attention.

Even if it’s messy.

Even if it’s expensive.

It’s right.

And I’m proud of us for trying.

Thank you.

And sorry for the typos - typing with one hand while holding my mom’s hand 😊

December 21, 2025 AT 18:12

Kaitlynn nail

So we’ve moved from ‘same pill’ to ‘same soul’?

How poetic.

But tell me - if a drug has the same total AUC and Cmax, why should we care about the curve?

Isn’t that just over-intellectualizing?

People have taken generics for 50 years.

They didn’t die.

They just saved money.

Now we’re turning bioequivalence into a philosophy seminar?

Next thing you know, they’ll require a soul scan.

Also - 127 guidances?

That’s not regulation.

That’s a novel.

And I’m tired of reading it.

December 23, 2025 AT 00:34

Rebecca Dong

THIS IS A COVER-UP.

They’re using pAUC to hide the fact that generics are being contaminated.

Did you know the FDA stopped testing for heavy metals in 2018?

Now they’re just measuring ‘time windows’ to distract you.

And the machine learning pilot? That’s AI trained on data from companies that bribed the FDA.

It’s all connected.

They don’t want you to know the real reason generics fail.

It’s not the curve.

It’s the toxins.

And if you ask the wrong question - you get banned.

Just wait - next year they’ll say ‘pAUC proves safety’ while the pills are laced with lead.

Wake up.

This isn’t science.

It’s propaganda.

December 24, 2025 AT 01:37

Regan Mears

Let me say this gently - but firmly: this is one of the most important developments in generic drug safety in a decade.

Yes, it’s complicated.

Yes, it’s expensive.

Yes, it’s messy.

But here’s the thing - we’ve been letting people take drugs that might as well be lottery tickets.

One day it works.

Next day - boom.

And no one knows why.

pAUC isn’t about bureaucracy.

It’s about dignity.

It’s about giving patients a fighting chance - not just a pill that ‘looks’ the same.

And yes - small companies will struggle.

But that’s why we need policy support - not backlash.

Let’s fund the CROs.

Let’s train the biostatisticians.

Let’s make this work - not because it’s easy.

But because it’s right.

And if you think this is overkill?

Then you’ve never watched someone suffer because their med didn’t hold steady.

I have.

And I’d rather have a $350k study than a $350k funeral.

Thank you for this post.

It’s a lifeline.

December 25, 2025 AT 05:00

Stephanie Maillet

There’s something deeply human about this.

We’ve spent centuries reducing medicine to molecules.

But bodies aren’t equations.

They’re rhythms.

They’re patterns.

They’re the quiet moments between peaks - the slow fade that keeps you alive.

Partial AUC isn’t a statistical trick.

It’s a meditation on timing.

It says: ‘We see you.

We see the hour you need relief.

We see the moment your body screams for stability.’

And for the first time - we’re designing medicine to honor that.

Not just the total dose.

But the dance.

The cadence.

The heartbeat of the drug.

It’s not perfect.

But it’s a step toward seeing patients as people - not just data points.

And that? That’s worth the cost.

That’s worth the effort.

That’s worth the tears.

And the typos.

And the sleepless nights.

Because medicine shouldn’t just work.

It should whisper to your soul.

And now - for the first time - it might.

December 26, 2025 AT 00:30

Aidan Stacey

Wait - so if the FDA’s machine learning pilot works, will they auto-generate pAUC windows?

And if so… who trains the AI?

Same labs that work for the brand?

Then it’s just bias in disguise.

Also - what if the ‘optimal window’ changes based on ethnicity?

Or age?

Or gut biome?

Are we going to need 12 different pAUC profiles for one drug?

And who pays for that?

And who gets left out?

Because if the AI was trained on 90% white male data?

Then the ‘optimal window’ for my grandma? Might be dead wrong.

So… is this progress?

Or just a new kind of algorithmic colonialism?

Just saying - we need transparency.

Not just automation.

December 27, 2025 AT 19:37