When you’re pregnant, every pill, injection, or even over-the-counter medicine you take doesn’t just stay with you. It travels through your bloodstream, crosses the placenta, and reaches your baby. This isn’t science fiction-it’s biology. And it’s more complex than most people realize.

The Placenta Isn’t a Wall. It’s a Gatekeeper.

Many assume the placenta acts like a shield, keeping everything harmful away from the baby. That’s a myth. The placenta is a dynamic, living organ that selectively lets some things through and blocks others. At full term, it weighs about half a kilogram, covers an area the size of a large dinner plate, and has a surface area of 15 square meters-roughly the size of a small apartment’s floor-for exchange between mother and fetus. It doesn’t just passively let drugs through. It actively decides. Some substances slip through easily. Others get pushed right back out. This is why two drugs with similar uses can have wildly different effects on a developing baby.How Do Drugs Actually Get Across?

There are four main ways medications cross the placenta:- Passive diffusion: Small, fat-soluble molecules move freely from high concentration (mom) to low concentration (baby). This is how alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine get through quickly.

- Active transport: Special proteins pump drugs in or out. Think of them as bouncers at a club-some drugs are allowed in, others are turned away.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis: The placenta grabs onto certain molecules like a handshake and pulls them inside. This is how some antibodies and large proteins enter.

- Facilitated diffusion: Drugs hitch a ride on transporters designed for nutrients, like glucose or amino acids.

- Molecular weight under 500 Da: More likely to cross. Most common drugs fall under this.

- High lipid solubility (log P > 2): Crosses 50-60% more easily.

- Ionized at body pH: Charged molecules struggle. Only about 10-20% of ionized drugs get through.

- Protein binding: If a drug is stuck to a protein in mom’s blood (like warfarin, which is 99% bound), it can’t cross. Only the free, unbound portion matters.

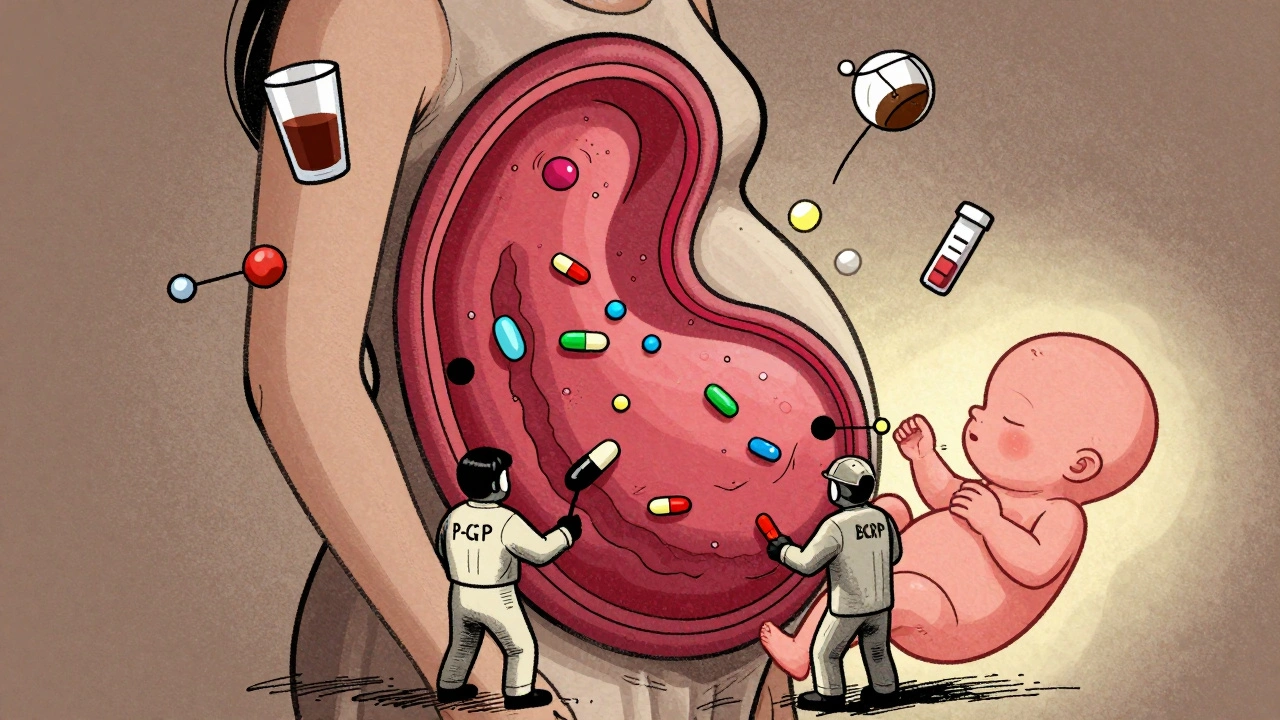

Transporters: The Body’s Drug Bouncers

The placenta has its own security system: ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Two of the most important are P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). These proteins act like pumps, shoving drugs back into the mother’s bloodstream before they reach the baby. This is why some medications barely reach the fetus-even if they seem like they should. For example:- HIV protease inhibitors like saquinavir and indinavir are actively pumped out. Their fetal concentration is only 1-3% of the mother’s. But if you block P-gp, those numbers jump by up to 2.3 times.

- Glyburide, a diabetes drug, only crosses at about 5.6% efficiency because BCRP keeps it in check.

- Digoxin, used for heart conditions, crosses easily-but not because it’s small or fat-soluble. It uses a different transporter. That’s why drugs like verapamil, which block P-gp, don’t affect it.

First Trimester: The Most Dangerous Window

You might think the placenta gets stronger as pregnancy progresses. Actually, it’s the opposite. In the first trimester, the placental barrier is still developing. Tight junctions between cells aren’t fully formed. Efflux transporters like P-gp and BCRP aren’t fully active. That means small molecules cross more easily early on. This is why many birth defects linked to medications-like thalidomide’s limb deformities in the 1950s-happen in the first 12 weeks. That’s when organs are forming. A drug that’s harmless later might be devastating now. Studies show the placenta is 2-3 times more permeable to small drugs in early pregnancy than at term. That’s not a minor difference. It’s a clinical red flag.

What Drugs Cross Easily? Real Examples

Here’s what actually gets through-and what doesn’t.| Drug Class | Example | Transfer Efficiency | Fetal Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants (SSRIs) | Sertraline | 80-100% | Neonatal adaptation syndrome in 30% of infants (jitteriness, feeding issues) |

| Opioids | Methadone | 65-75% | Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 60-80% of babies |

| Antiseizure | Valproic acid | 90-100% | 10-11% risk of major birth defects (vs. 2-3% baseline) |

| Antiseizure | Phenobarbital | 95% | Neonatal sedation, withdrawal symptoms |

| Chemotherapy | Paclitaxel | 25-30% | Can cause fetal growth restriction; increases to 45-50% with P-gp inhibition |

| Antibiotics | Penicillin | Low to moderate | Generally safe; minimal fetal exposure |

| Large molecules | Insulin | <0.1% | Does not cross; safe in pregnancy |

| Alcohol | Ethanol | Equal to maternal | Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders |

Why Some Drugs Are Riskier Than Others

It’s not just about how much gets through. It’s about what the baby’s body can do with it. A fetus doesn’t have a fully developed liver. It can’t break down drugs the way an adult can. Its kidneys don’t filter well. Its blood-brain barrier is still forming. So even a small amount of a drug can build up and cause lasting harm. For example:- Valproic acid crosses easily and directly interferes with fetal neural tube development. That’s why it’s linked to spina bifida and autism risk.

- SSRIs cross in high amounts but don’t cause structural defects. Instead, they can trigger temporary breathing and feeding problems after birth.

- Methadone crosses almost as well as it does in mom. The baby becomes dependent. Withdrawal after birth isn’t a side effect-it’s a direct result of fetal exposure.

What About Newer Drugs and Nanotech?

Pharmaceutical companies are now designing drugs to target the placenta-either to protect the fetus or to treat it directly. Nanoparticles, for example, could deliver oxygen or gene therapies to a developing baby. But here’s the catch: if those nanoparticles get stuck in the placenta, they could cause inflammation or block nutrient flow. Early studies show some nanomaterials accumulate in placental tissue, which might harm development. There’s also a growing market for placenta-targeted delivery-projected to hit $285 million by 2028. But safety data? Still limited. Most research uses animal models, and mouse placentas are 3-4 times more permeable than human ones. That’s a big problem.

Regulations Are Catching Up

After the thalidomide disaster, the U.S. passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendment in 1962, requiring proof of safety before a drug hits the market. But for decades, pregnant women were still left out of clinical trials. That’s changing. Since 2015, the FDA requires drug labels to include specific data on placental transfer and fetal risk. New drugs must now include quantitative transfer studies-how much gets through, under what conditions, and what the fetal exposure levels are. The European Medicines Agency now says: “Placental transfer potential must be evaluated early in drug development.” Still, 45% of prescription drugs on the market today have no reliable data on pregnancy safety. That’s not a gap. It’s a risk.What Should You Do?

If you’re pregnant or planning to be:- Don’t stop prescribed meds without talking to your doctor. Untreated depression, epilepsy, or high blood pressure can be more dangerous than the medication.

- Ask about placental transfer. Not all doctors know the details. But you have the right to ask: “Does this cross the placenta? How much? What’s the risk?”

- Use the lowest effective dose. Especially in the first trimester.

- Track your meds. Keep a list of everything you take-even herbs, supplements, and OTC painkillers.

- Consider therapeutic drug monitoring. For drugs like digoxin, lithium, or antiseizure meds, checking blood levels helps ensure you’re getting the right dose without overexposing the baby.

Comments

Taya Rtichsheva

so the placenta is basically a bouncer with a PhD and zero chill

also why is my coffee still getting through like i didnt even try

December 8, 2025 AT 22:31

Christian Landry

this is wild lol i always thought the placenta was like a forcefield

turns out it's more like a bouncer who lets in the cool kids (fat soluble drugs) and kicks out the weirdos (charged molecules)

also why does my prenatal vitamin feel like it's doing nothing? 🤔

December 9, 2025 AT 11:16

Kathy Haverly

so you're telling me after 40 years of medical research we still don't know what half these drugs do to babies?

and you want me to trust a doctor who 'probably' knows what's safe?

lol. i'm not pregnant but i'm already terrified.

December 10, 2025 AT 17:35

Chris Marel

this is actually really helpful. i'm a dad-to-be and i've been asking my partner all these questions but never knew where to start. thanks for breaking it down like this. the part about first trimester permeability really hit home.

December 10, 2025 AT 22:34

Evelyn Pastrana

soooo... if i take tylenol is my baby getting a little buzz?

also why does everyone act like pregnancy is magic when it's just biology with extra steps? 🙄

December 11, 2025 AT 20:30

Nikhil Pattni

actually this is all wrong. i read a paper in 2018 where they proved that placental transfer is mostly governed by maternal gut microbiome composition, not molecular weight or lipid solubility. the whole P-gp thing is outdated. also, if you're taking SSRIs, you should be on fluoxetine, not sertraline, because of the 17% higher placental transfer in the second trimester. and don't even get me started on how the FDA ignores epigenetic effects. i've been studying this since med school and honestly, the system is broken. 🤯

December 13, 2025 AT 16:40

Elliot Barrett

this is just a fancy ad for pharmaceutical companies to sell more expensive prenatal tests

we've been told not to take meds for decades and now they're telling us to take them? pick a side.

December 14, 2025 AT 04:03

Sabrina Thurn

the key takeaway here is the distinction between transplacental transfer and fetal pharmacokinetics. just because a drug crosses doesn't mean it's teratogenic. fetal hepatic metabolism, renal clearance, and blood-brain barrier maturity are the real determinants of risk. for example, sertraline crosses efficiently but has minimal neurodevelopmental impact, whereas valproate's mechanism directly disrupts histone deacetylase activity in neural crest cells. the clinical implication? Risk stratification must be drug-specific, not class-wide.

December 14, 2025 AT 13:43

Richard Eite

USA makes the best drugs. if you're in europe or canada you're just lucky if your baby survives. trust the science, not the fear.

December 15, 2025 AT 00:28

Philippa Barraclough

I find it fascinating how the placenta's transporter expression evolves dynamically across gestation. The upregulation of BCRP and P-gp in the second trimester is a protective adaptation, yet the literature still treats placental permeability as static. This has profound implications for timing of teratogenic exposure and dosing regimens. I wonder if longitudinal placental biopsy studies could quantify transporter density changes in real time - though ethically, that's a minefield.

December 15, 2025 AT 09:36

Olivia Portier

you guys are overthinking this

just ask your doc 'is this safe for my baby?'

if they hesitate, find a new one

and yes, i took ibuprofen at 8 weeks and my kid is now a genius at chess

so chill

December 15, 2025 AT 14:34

Lauren Dare

the fact that we're still using 'safe in pregnancy' as a clinical category without quantitative fetal exposure data is a joke. it's not that these drugs are 'safe' - it's that we have no idea what they're doing. the placebo effect of reassurance is doing more harm than good.

December 15, 2025 AT 19:42

Gilbert Lacasandile

this is really well written. i'm a nurse and i've seen moms panic over a single Advil. it's good to see someone explain the real science behind it instead of just saying 'avoid everything'.

December 17, 2025 AT 18:01

Lola Bchoudi

the placenta-on-a-chip models are the future. we're already seeing 3D bioprinted placental tissues with functional syncytiotrophoblasts and transporter expression mimicking gestational age. within five years, we'll be able to test drug transfer in vitro for individual patients based on their genetic transporter profiles. personalized prenatal pharmacology is coming - and it's long overdue.

December 19, 2025 AT 02:59

Morgan Tait

this is all part of the government's plan to control pregnancies. they don't want you to know that the placenta can be 'hacked' with certain frequencies and crystals. i've been using quartz crystals on my belly since week 6 and my baby's heart rate is perfectly balanced. the FDA knows this but they're scared of losing pharma profits. also, glyphosate is in your water. drink filtered water. and stop eating wheat.

December 19, 2025 AT 05:44