When a generic drug company wants to prove their version of a medication works just like the brand-name version, they don’t just guess. They run a crossover trial design. This isn’t just a common method-it’s the gold standard. More than 89% of bioequivalence studies submitted to the FDA in 2022 and 2023 used this approach. Why? Because it cuts out the noise. Instead of comparing different people, you compare the same person before and after taking each version of the drug. That’s the core idea.

How a Crossover Trial Works

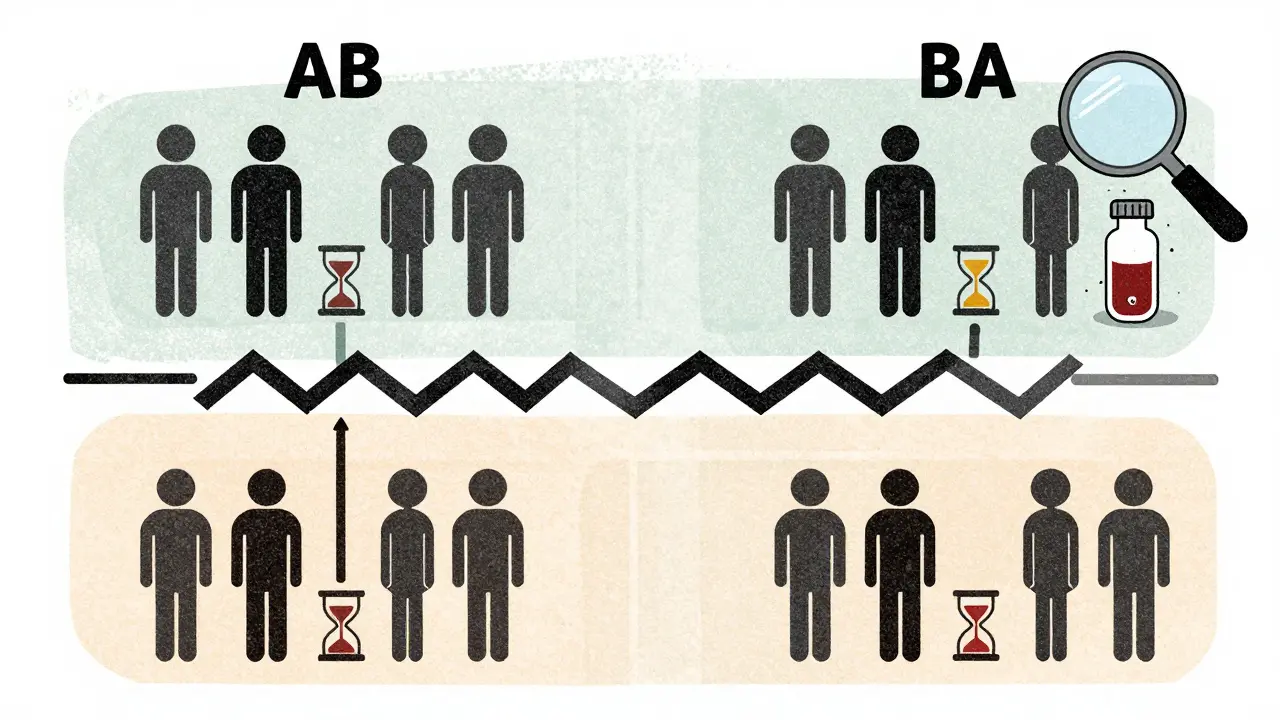

Imagine you’re testing two versions of the same pill: one made by the original brand, and one made by a generic company. In a crossover trial, every participant gets both pills-but not at the same time. They take one first, wait a while, then take the other. Half the group takes the brand-name drug first (let’s call that sequence AB), and the other half takes the generic first (sequence BA). This is called a 2×2 crossover design. It’s simple, efficient, and powerful.The key is the washout period. After finishing the first treatment, participants wait until the drug is completely out of their system. For most drugs, that means waiting at least five half-lives. If a drug clears the body in 8 hours, you wait 40 hours. For drugs that take days to clear, like some antidepressants, this becomes a major logistical hurdle. That’s why crossover designs don’t work for every drug. If the half-life is longer than two weeks, you can’t realistically wait long enough between doses. In those cases, parallel designs (where one group gets Drug A and another gets Drug B) are the only option.

Why It’s More Accurate Than Parallel Designs

In a parallel study, you compare Group A to Group B. But people are different. One group might be younger, healthier, or metabolize drugs faster. Those differences can hide the real effect-or make it look bigger than it is. In a crossover design, each person is their own control. That removes nearly all of that variability. The result? You need far fewer people to get the same level of confidence in your results.Here’s the math: if the differences between people are twice as big as the natural variation in how one person responds to the same drug, a crossover design needs only one-sixth the number of participants as a parallel design. So if a parallel study needs 72 people, a crossover might only need 12. That saves money, time, and resources. One clinical trial manager in Australia saved $287,000 and eight weeks by switching from a parallel to a crossover design for a generic warfarin study. That’s not rare-it’s standard practice.

When Things Go Wrong: Washout Failures

The biggest mistake in crossover trials? Getting the washout period wrong. If the drug hasn’t fully cleared the body before the second dose, it interferes with the results. That’s called a carryover effect. And it’s one of the most common reasons bioequivalence studies get rejected by regulators.A statistician on ResearchGate shared a story where his team’s study failed because they assumed a 48-hour washout was enough for a drug with a 12-hour half-life. But they didn’t check actual blood levels. Turns out, residual drug was still detectable. The second period’s data was contaminated. They had to restart the study with a 4-period replicate design-costing $195,000 more and adding months to the timeline.

Regulators like the FDA and EMA require proof that washout worked. That means measuring drug concentrations in blood samples at the end of each period to confirm they’ve dropped below the lower limit of quantification. It’s not optional. It’s mandatory. Skipping this step isn’t just bad science-it’s a regulatory red flag.

Replicate Designs for Trickier Drugs

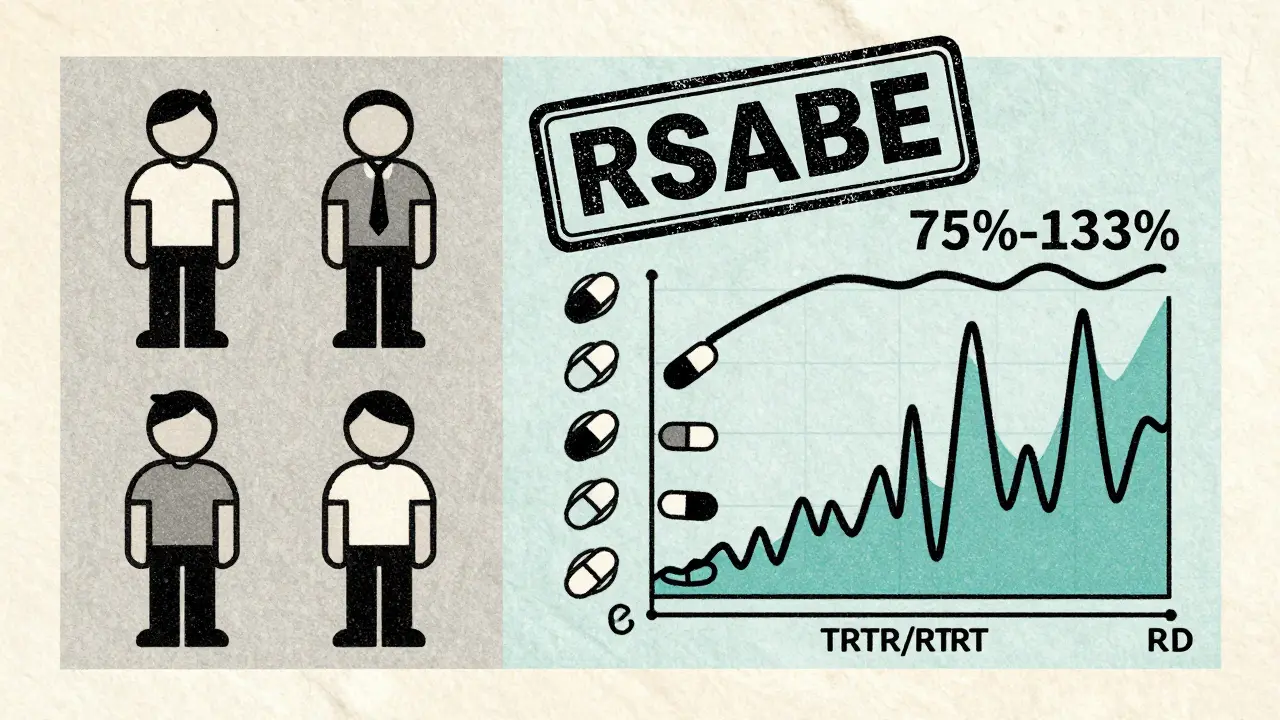

Not all drugs behave the same. Some have high variability-meaning the same person’s response can swing wildly from one dose to the next. If the intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) is over 30%, standard 2×2 designs become unreliable. The confidence intervals get too wide. The study might fail even if the drugs are truly equivalent.That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of giving each drug once, you give each drug twice. The most common are:

- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Test drug once, reference drug twice

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Test and reference each given twice

These designs let regulators calculate within-subject variability for each drug separately. That’s critical for something called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). With RSABE, the acceptable range for bioequivalence isn’t fixed at 80-125%. For highly variable drugs, it can widen to 75-133.33%. That’s a game-changer. In 2015, only 12% of highly variable drug approvals used RSABE. By 2022, that number jumped to 47%. It’s the fastest-growing trend in bioequivalence.

Statistical Analysis: What Happens Behind the Scenes

It’s not enough to just give the pills and measure blood levels. The data needs careful analysis. Regulators require linear mixed-effects models using software like SAS (PROC MIXED) or Phoenix WinNonlin. The model checks three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order of drugs affect the outcome?

- Period effect: Did time itself change the response (like seasonal changes or learning effects)?

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the test and reference drugs?

If the sequence-by-treatment interaction is significant, that’s a red flag-it suggests carryover. The study may need to be rejected or redesigned. Missing data is another trap. If someone drops out after the first period, their data can’t be used in a crossover design. Unlike parallel studies, where you can still analyze partial data, crossover relies on paired comparisons. One missing value breaks the pair. That’s why dropout rates are kept under 10%.

What the Regulators Say

The FDA and EMA both say crossover designs are the preferred method for bioequivalence studies. The FDA’s 2013 guidance explicitly states: “A crossover study design is recommended.” The EMA’s 2010 guideline echoes this. But they’re not just asking for a design-they’re asking for rigor. Documentation must show:- Randomization at the sequence level (not individual assignment)

- Validation of washout periods with pharmacokinetic data

- Statistical models that account for period and sequence effects

- Clear justification for using replicate designs

Companies that skip these steps often get rejection letters. In 2018, about 15% of major deficiencies in FDA submissions were due to poorly designed washouts or incorrect statistical models. That’s not a small error-it’s a preventable failure.

What’s Next? Adaptive and Digital Designs

The field is evolving. Adaptive designs are gaining traction. These allow researchers to adjust sample size mid-study based on early results. In 2018, only 8% of FDA submissions used this approach. By 2022, it was up to 23%. It’s a smarter way to handle uncertainty-especially with highly variable drugs.There’s also talk about digital monitoring. Wearables and continuous glucose or drug sensors could one day replace the need for multiple blood draws. Imagine tracking drug levels in real time without ever drawing blood. That could shrink washout periods or even eliminate them. It’s still experimental, but it’s the kind of innovation that could redefine bioequivalence testing in the next decade.

Bottom Line: Crossover Is Still King

For now, the crossover design remains the most reliable, cost-effective, and scientifically sound way to prove bioequivalence. It’s not perfect. Washout periods are tricky. Carryover effects can sneak in. Replicate designs add cost and complexity. But when done right, it gives regulators confidence that a generic drug is just as safe and effective as the brand.For generic manufacturers, it’s the difference between a quick approval and a costly, months-long redo. For patients, it’s the assurance that the cheaper version they’re taking works just as well. And for science, it’s a brilliant example of how smart study design can turn a complex problem into a clear, answerable question.

Why is a crossover design better than a parallel design for bioequivalence studies?

A crossover design uses each participant as their own control by giving them both the test and reference drugs in sequence. This removes differences between people-like age, weight, or metabolism-from affecting the results. Because of this, crossover studies need far fewer participants to achieve the same statistical power. In some cases, you can cut the sample size by up to 80%. That makes studies faster, cheaper, and more ethical since fewer people are needed.

What is a washout period, and why is it so important?

A washout period is the time between two treatment phases in a crossover study, during which participants don’t take any study drugs. It’s designed to let the first drug completely leave the body before giving the second one. If the drug is still present, it can interfere with the second dose, leading to false results. Regulators require washout periods to be at least five half-lives of the drug. Evidence-like blood test results showing drug levels below detection limits-must be provided to prove it worked.

When should a replicate crossover design be used?

Replicate designs (like TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs-those where the same person’s response varies by more than 30% between doses. Standard 2×2 designs can’t reliably detect equivalence for these drugs because the variability swamps the signal. Replicate designs let regulators estimate within-subject variability for both drugs, which allows them to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). This method widens the acceptable bioequivalence range, making approval possible without needing hundreds of participants.

What’s the standard bioequivalence acceptance range?

For most drugs, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) must fall between 80.00% and 125.00% for both AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration). For highly variable drugs, regulators allow a wider range-75.00% to 133.33%-but only if a replicate crossover design is used and reference-scaled bioequivalence (RSABE) is applied. This is not a loophole-it’s a scientifically validated adjustment for drugs where normal limits would make approval impossible.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives-typically longer than two weeks. Waiting five half-lives for such drugs could mean months between doses, which isn’t practical or safe for participants. In these cases, parallel designs are required. Examples include some long-acting injectables, certain psychiatric medications, and drugs like terbinafine. Regulators will reject a crossover study for these drugs unless the sponsor can prove a scientifically justified alternative.

What software is used to analyze crossover trial data?

The most commonly used software in industry is Phoenix WinNonlin, which has built-in templates for crossover analysis. SAS (using PROC MIXED or PROC GLM) is also widely used, especially in regulatory submissions. Open-source tools like the R package ‘bear’ are gaining popularity among academic researchers but require advanced programming skills. The key is not the software-it’s using the correct statistical model: a linear mixed-effects model that accounts for sequence, period, and subject effects.

Comments

Christopher King

This is all just a front. The FDA and Big Pharma are using crossover trials to hide the fact that generics are literally different drugs. They tweak the inactive ingredients just enough to make it *seem* like it works the same, but your body knows. I’ve had seizures switching brands. They don’t want you to know this.

December 24, 2025 AT 19:56

Bailey Adkison

Crossover trials are not the gold standard they claim. The term is misused. Gold standard implies flawless methodology. But carryover effects are systemic and often ignored. The data is contaminated. The math is cherry-picked. And the word 'bioequivalence' is a legal fiction not a scientific one.

December 26, 2025 AT 04:59

Michael Dillon

Honestly the whole thing is overengineered. You don’t need 12 people. You need one person who’s willing to take both pills and tell you which one made them feel better. The rest is just corporate theater to justify $2 million in lab fees.

December 27, 2025 AT 21:32

Katherine Blumhardt

I read this and thought wow this is so cool 😍 but then I realized I have no idea what half the words mean 😅 like what’s a washout period again? is it like a detox? 🤔

December 29, 2025 AT 13:10

sagar patel

The statistical models used are flawed because they assume normal distribution of pharmacokinetic data which is rarely true. This is why so many studies fail. The math is wrong from the start

December 29, 2025 AT 18:32

Linda B.

So let me get this straight. We’re trusting the same corporations that priced insulin at $300 a vial to run perfectly clean trials? With a washout period they didn’t even measure? Please. This is how people die quietly.

December 30, 2025 AT 08:47

Terry Free

You’re overcomplicating this. The FDA doesn’t care about your fancy mixed models. They care if the generic doesn’t kill people. If the blood levels are within 80-125%, it’s fine. The rest is academic noise.

January 1, 2026 AT 08:01

Sophie Stallkind

The elegance of the crossover design lies in its ability to isolate treatment effects from inter-individual variability. This is not merely a statistical convenience; it is a fundamental principle of experimental control that minimizes confounding factors. One must acknowledge the rigor required to implement such a design appropriately.

January 2, 2026 AT 01:30

Carlos Narvaez

Crossover design? More like crossover illusion. You think you’re controlling variables but you’re just hiding noise behind fancy math. Real science doesn’t need SAS.

January 2, 2026 AT 09:41

Harbans Singh

I’m from India and we use generics every day. This stuff matters. But I wonder - if the system is so perfect, why do so many patients still report different effects? Is it the drug? Or the way we test it? Just asking.

January 3, 2026 AT 06:22

Zabihullah Saleh

There’s something poetic about this. Same body. Two pills. One question: are they the same? It’s like asking if two versions of the same song sound identical when played by the same musician. The answer isn’t in the notes - it’s in the silence between them.

January 3, 2026 AT 21:24

Rick Kimberly

The assumption that a five-half-life washout is sufficient is empirically unsupported for many drugs with nonlinear pharmacokinetics. Regulatory guidelines have not kept pace with pharmacological complexity. This is a systemic vulnerability.

January 5, 2026 AT 06:37

Oluwatosin Ayodele

This is why Africa can’t get affordable meds. You all are so busy arguing over statistical models you forget people are dying waiting for these studies to finish. Just make the damn drug cheap and test it in the real world.

January 5, 2026 AT 16:20